Night owls of Canada

Noctuae canadensis

—Feral

Noctuae Canadensis

Noctuae canadensis is one movement of a longer composition, Woodwings, which was originally written as a commission from Fifth Wind Quintet with funding from the Canada Council for the Arts to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Canada. The theme of the concert was past, present, and future, but I did not want to write a piece about Canada as a country, because of its problematic colonialist origins. Instead, I wanted to explore the landscape and soundscape of the lands now called Canada—something that would explore a kind of continuity from before European settlement to today to what I hope will be a more equitable future. Of course, the soundscape is changing as well—there are sounds we had in the past that we no longer have now, or sounds that are endangered now, and of course new sounds come into the soundscape, particularly those coming from technology. But I was thinking about at least, the possibility of a continuity of soundscape. People might have heard the same species of owls 150 years ago, and I hope they will hear the same owls 150 years from now.

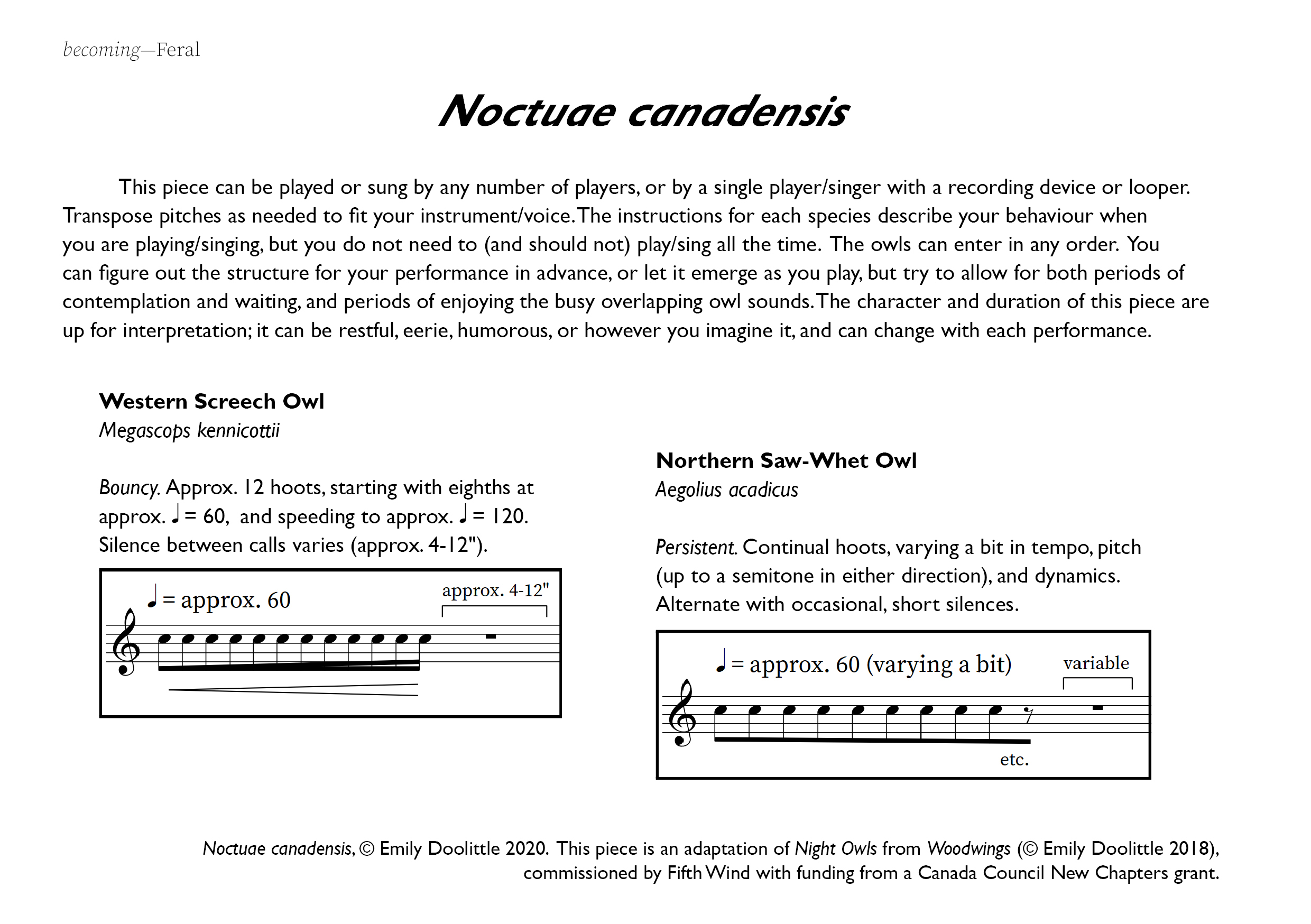

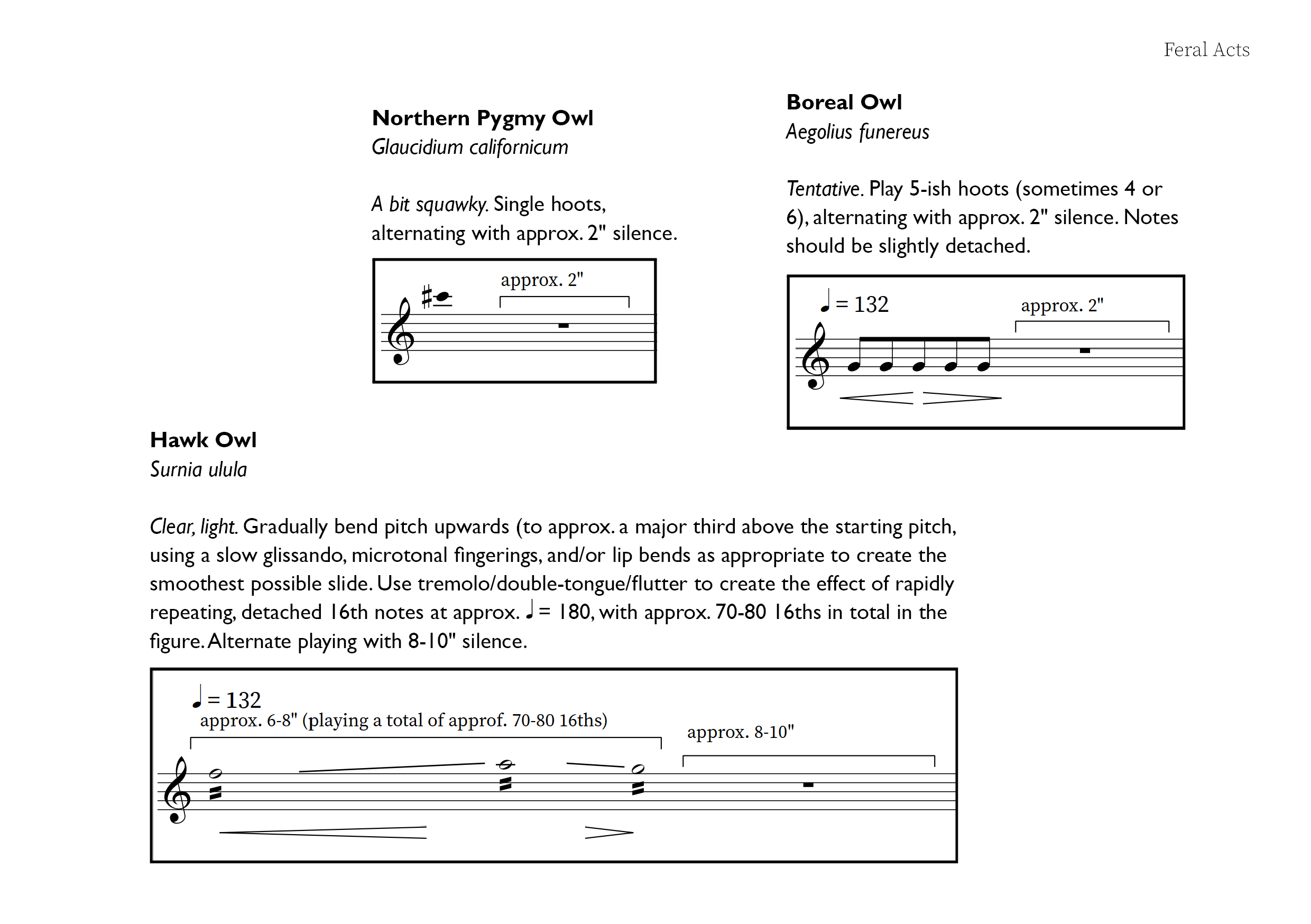

There are nine species of owls that live in Canada, and this composition presents five owls’ calls in an improvisational format. I was not trying to recreate the sounds of any particular ecosystem: indeed, these five species would never be found all together. This version of the piece can be played on any instrument or sung, and could be performed by any number of musicians. If someone is playing it alone, they might want to use an audio recorder or looper to create multiple layers of overlapping owl sounds. But of course, engagement with the score does not have to end with an indoor performance. Perhaps someone might want to bring these performed owl sounds outside. (Just make sure you do not annoy any actual owls living there.) Or perhaps this score might spark peoples’ curiosity about the sounds of the animals that live around them. Or maybe they’ll remember an animal sound they haven’t heard for a while and try to go hear that again. Maybe they’ll be inspired to write their own piece based on environmental sounds. This score should be seen as a starting point—a stimulus—not an endpoint.

Emily Doolittle

Research Fellow and Lecturer in Composition,

Royal Conservatoire of Scotland

—Glasgow, Scotland

(originally from Halifax, Canada)

Score

Interview with Emily Doolittle (by Josh Armstrong)

JA: I wonder how you would describe zoomusicology.

ED: It’s quite a new field or area of study. The word itself has been in use since the 1980s; it was coined by a French composer, François-Bernard Mâche, referring to his own work looking at animal songs both in his music and his research. And then, an Italian semiotician and musicologist, Dario Martinelli, started to develop it as an academic field beginning in the ’90s.

I’d say there’s probably only about 20 researchers in the world who might describe themselves as zoomusicologists, and I think each of us has a slightly different take on it.

For me, zoomusicology is the study of the music-like sounds created by non-human animals. This leaves aside the question of whether animal songs are music or not because there’s no single definition of music that works for all music. I think many of us feel like there’s enough similarity between some animal songs and some human music that some tools of musicological and music theoretical analysis may be helpful for looking at animal songs, and simultaneously, some tools of biological analysis may be helpful for looking at human music.

JA: Part of the question I have regarding zoomusicology is, who is it for? Is it for humans to understand the world better, or is there any benefit to other-animals?

ED: Like any human field of study, it’s primarily designed for humans to try to understand the world around us, and probably even when we think we’re doing something for other species, we’re really just doing it to make ourselves more comfortable. I do hope that in coming to understand animal song and non-human creativity better, we might also come to have more respect for preserving habitat and making sure the world is a good place for all species to live in.

One of the things that really interests me as a zoomusicologist is looking at the individuality of what each animal sings. We often think, “Oh, there’s a bunch of birds outside,” or maybe if we know a little more about birds, we think there’s a bunch of Starlings outside, or a bunch of European Blackbirds, or there’s a bunch of Wood Pigeons (there are always a lot of Wood Pigeons!). I’m really interested in going beyond that to ask, what is this individual Blackbird singing and how does its sound differ from how that Blackbird over there sings?

We’re so used to thinking about people as individuals and thinking about our own aesthetic preferences, but we typically don’t extend that awareness of individuality to other-animals. Of course, they’re a member of their species, and that will say a lot about how they act and what they do, but it won’t say everything about how they act and what they do, just as us being members of the human species doesn’t say everything about who we are and what we do.

JA: That is really fascinating. In some sense is there a link here to practices of ethnomusicology?

ED: There are both helpful and problematic ways in which zoomusicology can be related to ethnomusicology. On the helpful side, I think there are many tools for listening to and conceptualizing music from ethnomusicology that can be really helpful for approaching sounds that may or may not be music and which come from a culture that’s really different than what we are familiar with. For example, a lot of people who are looking at the question of whether some animal songs are music have studied the literature about human musical “universals.” I mean, the literature about musical universals is in itself problematic: it tends to be written from a very Western-centric perspective, and there is probably nothing that is “universal” that applies to absolutely all music— but nonetheless looking at traits that are found in a wide variety of human music might suggest things we might want to investigate in animal songs as well. So, if the question is “can an ethnomusicological approach help us study animal songs?,” the answer is very much so. (Just as ethnomusicological approaches can help us study Western classical music, it’s an artefact of colonialism that musicology and ethnomusicology are considered separate fields).

But there’s also a long and disturbing history of people equating music by people who were not classically trained white European classical musicians with music by animals. And although I don’t think many present-day researchers would still subscribe to this view, vestiges of it remain in how we talk about animal song. To give just one example, the hermit thrush is a North American bird whose song is widely considered “beautiful.” In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, musicians and scientists alike praised the song by describing it as following the rules of Western classical music. Obviously, no bird would actually be following the music theoretical rules of a human musical culture— this idea comes from these researchers’ problematic conviction that there was something “natural” about Western classical music, so it must be found in animal songs as well. But things got even worse in about 1920 when people got the idea that birds with beautiful songs, like the Hermit Thrush, must sing the same kinds of songs as so-called “primitive” human musicians. Of course, there is no such thing as “primitive” people or “primitive” music: all cultures and all kinds of music existing today have been developing and evolving for exactly the same amount of time. But these early 20th century researchers were convinced that birds were “primitive” musicians, and “primitive” music must all be based on “the pentatonic scale,” so therefore hermit thrush song must be based on “the pentatonic scale.” Of course, the idea of “the pentatonic scale” is also problematic: lots of cultures may have 5-note scales, just as they may have 6-, 7-, 8-, or 9-note scales, but there’s no such thing as a universal “pentatonic scale.” A 5-note scale will be configured and conceptualized differently in each musical culture that has one. Nonetheless, there are several early-20th century scientific papers that claim to find “the pentatonic scale” in hermit thrush song, and even though this has been disproven, the myth about the hermit thrush singing the pentatonic scale is repeated to this day. (For further reading on the history of how people talk about and represent animal songs, there’s a great book by Rachel Mundy: Animal Musicalities).

JA: The more we have been thinking through the wild/feral/domestic, the more clear it has become that the tools of domestication are often tools of control— control in the forms of colonialism and capitalism.

You have been working with bird song in a variety of ways in your compositions. What is your perspective on the process of working with these sounds and songs? Would you describe it as translation or interpretation?

ED: Most of my birdsong-based pieces are based on the songs of songbirds—scientifically called Oscine passerines—which are the birds who learn their songs. Most of the birds we think of as having beautiful songs like Wrens, Robins, Blackbirds would fall into this category—if they don’t hear their song sung by other members of their species when they are young, they won’t learn to sing it. This process is called “vocal learning” and is found in 5000 species of songbirds, as well as in hummingbirds and parrots. Vocal learning is less common in mammals, but whales, dolphins, seals, bats, elephants, and of course humans do it, too. (Interestingly, no other primates are known to be vocal learners).

So, most of my bird compositions have been based on the songs of Oscine passerine because I’m really interested in the cultural aspects of animal songs. For me, the idea that some animal song is learned is an even more important aspect of its connection with human music than just how it sounds. I’m also fascinated by how learned animal songs can be both cultural and individual: for example, with blackbirds, every time you hear one sing you can recognize immediately what species it is, but you can also distinguish individuals within the species. It’s the same with human music: we learn music from other people around us, but then there’s also individuality within how each person might interpret the music they learned.

For many of my other pieces, I do think of them as translations. Songbirds tend to process sound much faster than we do, so when we listen to a bird singing, we’re not actually hearing what members of that bird species hear because they can understand things that are so much faster and so much higher. Often, we need to slow things down and bring them into a range or timbre that’s more comfortable for us to be able to fully appreciate what’s going on within the song. I think of this as a kind of translation because I’m trying to present the song to human listeners in a way that we can get closer to it. Then, I often blend it with my own musical ideas: the piece becomes a sort of hybrid between my understanding of the bird song, and the music that it suggests to me. I don’t perform my own music, so there’s also how the performer will then translate what I give to them. So, there’s at least two levels of translation before the audience will hear the bird song, and of course they bring to that their own preconceptions, as well.

And just, you know, this kind of translation can sometimes work both ways because there are also non-human animals that might imitate human sounds. For example, European Blackbirds can imitate, and sometimes they’ll imitate a phone ringing or a car alarm or something else like that. They hear a sound they like, and they take it and put it in their own song. Maybe they hear a cat meow, and they might copy that. When they make the sound of a cat, they are not communicating the same thing a cat is with a meow but are incorporating the sound itself into the structures and grammar of their own song. I have to say, I’m especially interested in working with the songs of species where the borrowing can go in both directions.

I do sometimes write music based on the calls of non-passerine birds, as well: birds that do not learn their calls, and Noctuae Canadensis would be one example. I’ve previously written music based on goose, gull, and grouse calls. But this is my first piece based on owl calls! In some ways, the process for this particular piece was different than many of my other pieces.

Noctuae Canadensis is one movement of a longer piece, Woodwings, which was originally written as a commission for Fifth Wind Quintet in Canada in celebration of the 150th anniversary of Canada as a country. The theme of the concert was past, present, and future and I was thinking the only constant is the landscape and soundscape itself. Of course, that is changing as well—there are sounds we had in the past that we no longer have now, or sounds that are endangered now, and of course new sounds come into the soundscape, particularly those coming from technology. But I was thinking about, at least, the possibility of the continuity of the soundscape. People might have heard the same species of owls 150 years ago, and I hope they’ll be hearing the same owls 150 years from now.

There are nine species of owls that lived in Canada, and for this piece I listened to all of them, and I chose the five I liked best. Of course, it’s important to remember that for each species they’re going to have their own preferences and dislikes so just because I think one owl sound is nicer than another, that doesn’t mean there’s anything objectively nicer about it—I just chose the sounds I wanted to work with!

This piece is not really a translation or a transcription; it’s more about entering into the experience of being in the woods at night. These five species of owls wouldn’t all be found in the same location; I wanted to bring together different bioregions together through sound. What these sounds have in common is that you might experience them under similar circumstances—in remote locations, at night—even in very different kinds of environments. But the piece does have a lot of freedom in how people can interpret it, so if someone wants to recreate the soundscape of a particular location, they could also do that.

The piece was premiered by a consortium of five wind quintets, and it was interesting to hear how different quintets approached it. One quintet wanted to recreate a sort of mystical night-time experience, so they turned off the lights in the concert hall. Everything was very quiet, and you hear the sounds as if coming from a long way off. Other groups focused on compositional structures that could be created with the owl-inspired sound elements. They were exploring ways to combine the overlapping patterns of the owl calls. There’s not a lot of variety in any of the owl calls. Some go up or down a little bit, but they don’t have complex sequences of different pitches. It’s more repeated notes in a certain rhythm, perhaps with a very gradually changing contour. But each species has its own tempo, its own number of repeats, its own contours. Then, other quintets thought of the humorous possibilities because it is sort of funny to be a person pretending to be an owl. In some cases, they played on the oboe and bassoon reeds and the clarinet mouthpiece and flute headjoint alone, detached from the main body of the instrument, to create a sound that was slightly more removed from usual musical associations.

JA: The work is exploring relationships between humans and other-animals, but also as the composer you’re designing a situation in which you give over control, which perhaps inherently lends itself to a kind of wildness.

ED: Yes, I think you’re right. Of course, this piece doesn’t need to be performed by professional musicians; anybody could realize it if they have something to make sound on. It’s not hard to repeat a single note with a little bit of contour. I was also just thinking that if somebody wanted, they could play it outside at night. This piece was inspired by sounds outside at night, and they could bring it back to the environment that inspired it! Of course, if you do something like that there are always questions like, are you actually intruding on the space of another creature? Is it going to be bothersome to an owl living there for you to go outside and play a sound that sounds like an owl? I don’t know. Perhaps the owl might find it reassuring to hear more owls around!

I don’t really have answers. I’ve written music to be performed outdoors, and I performed other people’s music outdoors, and I really like site-specific outdoor works. But I do think there is an ethical question of where you are performing and what other species are going to hear it. Do they have the choice to come close if they want to? Do they have the choice to go far away if they want? Are you disturbing any nesting habitats?

I have a student, Alex South, who’s studying Humpback Whale song from an interdisciplinary musical and scientific perspective. He’s being co-supervised by me and two biologists. Recently, we were all discussing the work of another researcher who was planning to play sounds for Humpback Whales underwater, and it was an interesting discussion because from a scientific point of view something like that is absolutely not ok. The idea of playing music for whales is considered unethical because you’re polluting their sound environment. And I absolutely understand where this is coming from. Especially when there’s such a long history of scientists killing animals to study them, it’s understandable why researchers of such an intelligent and sentient species would want to distance themselves from anything that might harm the animal in any way. But at the same time, I think about all the shipping noises in the world, all the underwater military tests, all the sound pollution that is already being added to every animal’s environment daily. Why is it that people might be horrified at the idea of playing music underwater for a whale, but they’re not up in arms about the ships that are crossing the oceans every day?

JA: Definitely, I think that’s really important. Speaking about the presence of the owls or other-animals in the playing of the piece, how do you position the owls within the performance and composition? Are the owls present as traces, or are they mostly present through their absence?

ED: I think people will have a different relationship to the piece depending on their experience of hearing owls. The piece has been performed in Europe, Canada, and the US so far. I think many, though not all, Canadians will have had the experience of hearing an owl, but fewer Europeans seem to have heard one in the wild. I lived in Seattle for seven years, and there was a problem with Barred Owls swooping on people and attacking their heads; several of my friends were attacked! So, people there may not have had the experience of hearing an owl in a magical night-time situation—their experience might be of being attacked. Or perhaps someone has had the experience trying to sleep somewhere, and there could be an owl that’s keeping them awake. We often think about all the magical experiences of hearing an owl at night, but if you’re hearing it at three in the morning and it won’t stop, you might have a very different relationship to the owl.

Of course, anyone playing the piece will bring their own experiences to it too—both their real-life experiences, and what they imagine. Whenever we’re hearing an owl, they are making their call for their own purposes, but when we hear it, we fit it into our lives and past experiences. Somebody who’s never heard an owl might think, “What is that strange sound?” and another person might be able to tell you, “Oh well, that’s a Barn Owl making that sound.” Somebody else might be able to say that it’s a juvenile Barn Owl. All of the different experiences the performers and audience bring with them will affect very much what kind of owl presence there is in the performance.

JA: As part of the collection, you are presenting a compositional score, which gives audiences a way to engage through action with this process of becoming-Feral—a provocation to engage in Feral Acts through the sonic composition.

ED: It would be cool if some people wanted to make this a performance by playing the score, but the act could be something else, too. Someone may think, “Oh, I don’t know what kinds of animals live around here, I’m going to go find out,” or they could think that it’s been a long time since they’ve heard an owl and decide to go camping. I think a lot of different kinds of acts could come from considering owl sounds.

JA: I think that’s a lovely thing. It goes back to what you were saying about an intention of zoomusicology to enable people to have a greater affinity with or awareness of other-animals in a variety of ways.

ED: Hopefully I would like to enable that through awakening people’s natural interest in and care for other-animals and environments.

I’ll tell you about an experience I had when lockdown began almost a year ago. I found it really hard to do anything and especially really hard to do any creative work. I was feeling so trapped in my room. Then, I got a commission to write a lockdown-related piece. I did what I often do when I’m starting a piece, which is to transcribe some animal songs. Usually, when I’m composing a piece based on animal songs, I’m thinking specifically about a song I’m interested in, or perhaps a particular bioregion that I want to explore the sounds of, but because this was a lockdown-related piece and I was really conscious of how I felt confined, I decided to transcribe the actual birds that came to our garden.

First of all, there was a Wood Pigeon that wouldn’t go away. It was always there, and that was the first thing that attracted my ear. But through being forced to pay attention to the Wood Pigeon, I realized that there were actually many other birds with more varied songs there. Even though I’m very interested in bird songs, I don’t tend to do a lot of birding where I live. And because I’m from North America, I know more about the American songbirds than British songbirds, so I decided this was a good opportunity to get to know more about birds that come to Scottish gardens.

I started transcribing what I heard and identifying the species. I realized that there was a European Blackbird that sang in the tree outside my window every day—the same Blackbird every day. They’re actually the species that got me interested in animal song some 23 years ago when I was living in the Netherlands for two years.

As I began transcribing the song of this Blackbird and began getting to know it as a piece of music, it became something familiar. I got to know the compositional tendencies of that particular Blackbird: if it’s just sung this motif, then usually after it sings that one, then it will sing this next one, but sometimes it goes to another one, and so on. I got to know that particular Blackbird song. There was a sense of comfort like when hearing a familiar piece of music.

Then when I went out walking, things started to become more interesting as well because when I would leave my own garden, I would hear other Blackbirds, and I would hear things they sang that were similar to what our Blackbird sang and things they sang that were different. I really appreciated getting to know one bird’s song so well through listening carefully for such a long period of time. That Blackbird came back for a few weeks early this spring, but then it moved on to somewhere else—I hope it moved on and nothing bad happened to it! No new Blackbird has moved into our tree yet, but hopefully we will have a new one in the spring!